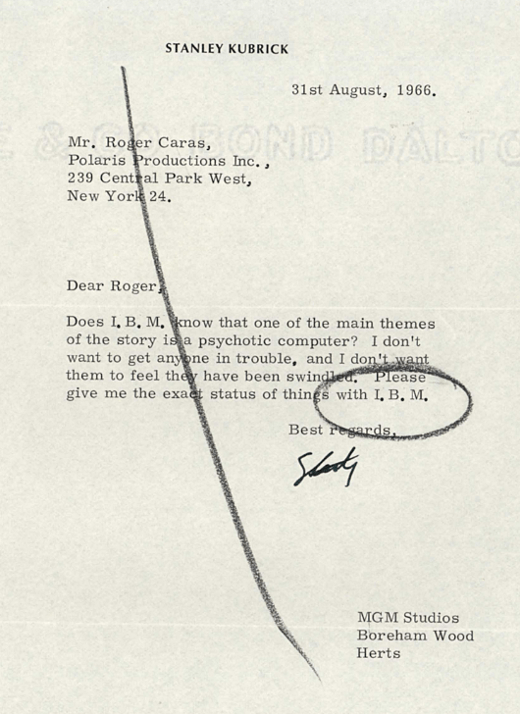

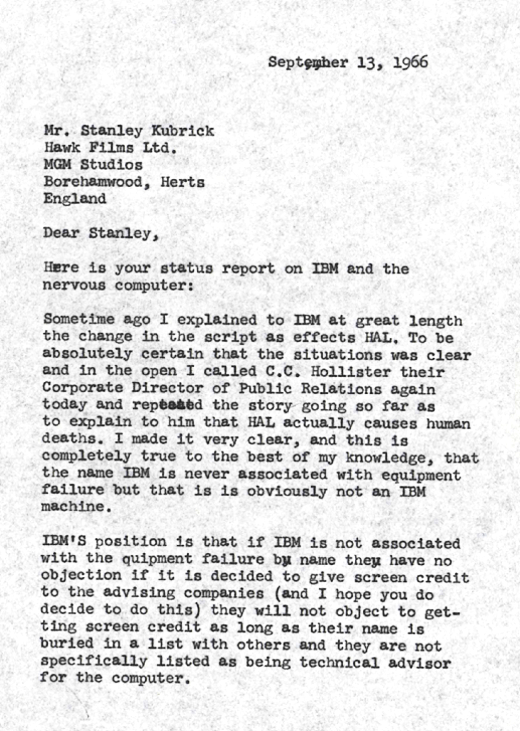

Stanley Kubrick worries about 2001: A Space Odyssey, from Letters of Note.

EIGHTY SIX

I’m writing, as I suppose will be usual this summer, from my balcony in St. Henri. I have a warm coffee filled with cardamom and honey, and the sun is shining down on the little box garden we planted last month. We’re growing snap peas and snow peas, cherry tomatoes and vine tomatoes, radishes and a dozen different herbs and spices. It’s a little crowded up here now, but we’ll have enough to share with the neighbours in a few months and it brings me a lot of joy to wake up in the morning and see how each plant has grown and changed. These moments are such blessings, to be able to breathe and reflect, but sometimes it makes me feel guilty. A project I have for the summer is to shake off that guilt for good.

The reality is that I have more work than I know what to do with—papers, briefs, reports to write, phone calls to make, budgets to revise, workshops to plan—but I’m not worried because it will inevitably get done. After years as an operative of the Cult of Busy, and years where busy-ness was more deeply part of my identity than I’d like to admit, I’m changing pace a little. There is tremendous pressure, especially I think in your mid-twenties, to define yourself by what you do rather than who you are. Part of clawing one’s way out of the quarter life crisis, at least for me, meant rejecting that pressure and seeking out space for an inner self.

Some of the deepest myths of capitalism come from the idea that progress is a tidy linear path onward and upward, that productivity has some inherent virtue. It’s those stories that make us anxious, that compel us to be busy for the sake of it, and most toxically, assert that busy-ness on others like some badge of honour and accomplishment.

I feel guilt off the clock because I feel like I could be doing more and therefore somehow being more: as though time spent gardening, having a drink with friends, practicing handstands and backbends or writing is somehow unproductive or valueless. I have a tattoo that reads vivez sans temps mort: a bit of an homage to the Situationists and a reminder from my younger self not to get complacent. At times I know I’ve used that line like a blunt weapon against myself, like this poisonous mantra reminding me to do all the things (!)—and fast. Of course that tendency is an ironic betrayal of the longer line the tattoo is born from, vivre sans temps mort et jouir sans entrave.

The reliance on full days and sleepless nights, either as a source of backwards pride or to inform a sense of self, is most destructive of all because it gets in the way of our ability to have long thoughts. To paraphrase a letter I wrote recently, it can be hard not to worry that years studying public policy better prepare you for a career writing dystopian science fiction than anything else. It’s precisely because the jadedness of Busy that comes along with it leaves just enough time for the social justice outrage machine but not enough for action. It lends you a moment to consider patching up holes but not enough to think about where the ship is headed.

So the project for the summer is thus: to nurture a more powerful kind of idleness, to stop being what I do, and to never feel guilty about sitting on the balcony again. And here is Mark Slouka, in Quitting the Paint Factory, on exactly this:

“A resuscitated orthodoxy, so pervasive as to be nearly invisible, rules the land. Like any religion worth its salt, it shapes our world in its image, demonizing if necessary, absorbing when possible. Thus has the great sovereign territory of what Nabokov called “unreal estate,” the continent of invisible possessions from time to talent to contentment, been either infantilized, rendered unclean, or translated into the grammar of dollars and cents. Thus has the great wilderness of the inner life been compressed into a median strip by the demands of the “real world,” which of course is anything but. Thus have we succeeded in transforming even ourselves into bipedal products, paying richly for seminars that teach us how to market the self so it may be sold to the highest bidder. Or perhaps “down the river” is the phrase.

Ah, but here’s the rub: Idleness is not just a psychological necessity, requisite to the construction of a complete human being; it constitutes as well a kind of political space, a space as necessary to the workings of an actual democracy as, say, a free press. How does it do this? By allowing us time to figure out who we are, and what we believe; by allowing us time to consider what is unjust, and what we might do about it. By giving the inner life (in whose precincts we are most ourselves) its due. Which is precisely what makes idleness dangerous. All manner of things can grow out of that fallow soil. Not for nothing did our mothers grow suspicious when we had “too much time on our hands.” They knew we might be up to something. And not for nothing did we whisper to each other, when we were up to something, “Quick, look busy.””

EIGHTY FIVE

Future Japanese, Yuko Shimizu.

EIGHTY FOUR

On the Edge, Chomsky in Pen.

“We might wish to consider a remarkable paradox of the current era. There are some who are devoting serious efforts to avert impending disaster. In the lead are the most oppressed segments of the global population, those considered to be the most backward and primitive: the indigenous societies of the world, from First Nations in Canada, to aboriginals in Australia, to tribal people in India, and many others. In countries with influential indigenous populations, like Bolivia and Ecuador, there is by now legislative recognition of rights of nature. The government of Ecuador actually proposed to leave their supplies of oil in the ground, where they should be, if the rich countries would provide them development aid amounting to a small fraction of what they would sacrifice by not exploiting their oil resources. The rich countries refused.

While indigenous people are trying to avert the disaster, in sharp contrast, the race toward the cliff is led by the most advanced, educated, wealthy, and privileged societies of the world, primarily North America.

There is now much exuberance in the United States about “100 years of energy independence” as we become “the Saudi Arabia of the next century.” One might take a speech of President Obama’s two years ago to be an eloquent death-knell for the species. He proclaimed with pride, to ample applause, that “Now, under my administration, America is producing more oil today than at any time in the last eight years. That’s important to know. Over the last three years, I’ve directed my administration to open up millions of acres for gas and oil exploration across 23 different states. We’re opening up more than 75 percent of our potential oil resources offshore. We’ve quadrupled the number of operating rigs to a record high. We’ve added enough new oil and gas pipeline to encircle the Earth and then some.”

It can be so hard not to just feel angry. This morning the news is filled with stories about rising oceans and the break in the West Antarctica ice sheet and I just can’t help but feel enraged about the lunacy of it all. And tired, too.

EIGHTY THREE

‘Help’ by Svjeeta.

EIGHTY TWO

Monika Umba’s speechless animation of “Bluebird“ by Bukowski, and two other animations of Bukowski’s poems.

EIGHTY ONE

Le bat, via this isn’t happiness.

EIGHTY

Every time I listen to this song I have this vivid memory of sitting on a curb in Jenin drinking turkish coffee, cool breeze, shockingly blue sky, early early morning, listening to Beirut.

SEVENTY NINE

Oh wow, this is totally how I feel when I think too much about germs! By Mateusz Kolek — whose art kind of reminds me of the This is Not a Toy exhibition I saw in Toronto last month.

SEVENTY EIGHT

Bill Zindel via the Jealous Curator.

SEVENTY SEVEN

SEVENTY SIX

“Let me tell you: one day you will renounce your exile, and you will go back home, and your mother will take out the finest china, and your father will slaughter a sprightly cockerel for you, and the neighbours will bring some potluck, and your sister will wear her navy blue PE wrapper, and your brother will eat with a spoon instead of squelching rice and soup through the spaces between his fingers.

And you, you will have to tell them stories about places not-here, about people that soaked their table napkins in Jik Bleach and talked about London as though London was a place one could reach by hopping onto an Akamba bus and driving by Nakuru and Kisumu and Kakamega and finding themselves there.

You will tell your people about men that did not slit melons up into slices but split them into halves and ate each of the halves out with a spoon, about women that held each other’s hands around street lamps in town and skipped about, showing snippets of grey Mother’s Union bloomers as they sang:

Kijembe ni kikali, param-param

Kilikata mwalimu, param-paramYou think that your people belong to you, that they will always have a place for you in their minds and their hearts. You think that your people will always look forward to your return.

Maybe the day you go back home to your people you will have to sit in a wicker chair on the veranda and smoke alone because, although they may have wanted to have you back, no one really meant for you to stay.”

From Okwiri Oduor, “My Father’s Head.” On the Caine Prize 2014 shortlist.

SEVENTY FIVE

“Please do, however, allow me to deliver one very personal message. It is something that I always keep in mind while I am writing fiction. I have never gone so far as to write it on a piece of paper and paste it to the wall: Rather, it is carved into the wall of my mind, and it goes something like this:

“Between a high, solid wall and an egg that breaks against it, I will always stand on the side of the egg.”

Yes, no matter how right the wall may be and how wrong the egg, I will stand with the egg. Someone else will have to decide what is right and what is wrong; perhaps time or history will decide. If there were a novelist who, for whatever reason, wrote works standing with the wall, of what value would such works be?”

Haruki Murakami, on accepting the Jerusalem Prize in Haaretz.

SEVENTY FOUR

“Caffeine Breakdown,” full series here, by Duygu Uzman from Istanbul.

SEVENTY THREE

Chomsky on Žižek (whole interview here):

“What you’re referring to is what’s called “theory.” And when I said I’m not interested in theory, what I meant is, I’m not interested in posturing–using fancy terms like polysyllables and pretending you have a theory when you have no theory whatsoever. So there’s no theory in any of this stuff, not in the sense of theory that anyone is familiar with in the sciences or any other serious field. Try to find in all of the work you mentioned some principles from which you can deduce conclusions, empirically testable propositions where it all goes beyond the level of something you can explain in five minutes to a twelve-year-old. See if you can find that when the fancy words are decoded. I can’t. So I’m not interested in that kind of posturing. Žižek is an extreme example of it. I don’t see anything to what he’s saying. Jacques Lacan I actually knew. I kind of liked him. We had meetings every once in awhile. But quite frankly I thought he was a total charlatan. He was just posturing for the television cameras in the way many Paris intellectuals do. Why this is influential, I haven’t the slightest idea. I don’t see anything there that should be influential.”