Ariel DeAndrea, “Last Hope,” oil on canvas.

ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY FOUR

Pure gold from Michael Mark Cohen on “The Douchebag: The White Racial Slur We’re All Been Waiting For.”

Do we really need a white racial slur? Is the vision of equality that we should aspire towards a world without the N-word or Douchebag? Maybe. Maybe it is. But as everyone who is not colorblind can plainly see, this is not yet that day.

For the time being, this is the vernacular critique of whiteness that we’ve always needed, and its been right before our eyes all along. The term douchebag, again used as we already use it, has the power to name white ruling class power and white sexist privilege as noxious, selfish, toxic, foolish and above all, dangerous.

Since the coming of colorblindness as the official ideology of neoliberal racism, we have needed a precise term with which to recognize and ridicule white privilege when we see it. So we should sharpen our critical swords and wield this insult with a new rapier like awareness, and thereby give the racists, the conservatives, and the 1% something they are always imagining anyways: reverse discrimination.

ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY THREE

Maya Hayuk, Toronto, 2011.

ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY TWO

I finally got around to getting a copy of ōgen / Matt Holubowski‘s album. You should too.

ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY ONE

Steven Orner, Very Happy to Be Here.

ONE HUNDRED AND SIXTY

This morning was really lovely. I ran into an old friend, which lead not only to a free coffee (!) but funny impressions of George Plimpton (who I had never really read about) and another film to add to my list.

Then it poured rain and I showed up to a lecture late, but that’s okay too.

My father’s voice was like one of those supposedly extinct deep-sea creatures that wash up on the shores of Argentina every now and then. It came from a different era, shouldn’t have still existed, but nevertheless, there it was—old New England, old New York, tinged with a hint of King’s College King’s English. You heard it and it could only be him.

So it was that George Plimpton’s accent could not be imitated. On “Saturday Night Live,” even the great impersonator Dana Carvey couldn’t get it quite right. Alan Alda, portraying my dad in the movie version of “Paper Lion” (his book on playing quarterback for the Detroit Lions), didn’t bother with his voice at all. He got the personality totally wrong, too. Alda’s version was always angry or consternated, like a character in a Woody Allen film, while my dad, though he certainly faced hurdles as an amateur in the world of the professional, bore his humiliations with a comic lightness and charm—much of which emanated from that befuddled, self-deprecating professor’s voice.

From Taylor Plimpton in the New Yorker.

ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY NINE

From Buck 65:

I remember the moment I discovered art.

The memory is a bit hazy. I was probably less than five years old. I was with my mother. We were in the decrepit home of a friend or acquaintance of hers. I can’t remember what the friend looked like except that she was big. Round. And I remember that the woman had scrawny, drunk boyfriend. He could barely talk. That frightened me. And they had a dog – a chihuahua, I think. I was very allergic to it. Strangely, it was the only dog to which I’ve ever had an allergic reaction. I just remember sneezing over and over and over again.

As my mother and her friend talked in the kitchen, I crept around the house. It was very old and smelled rotten. It was falling apart. I remember a treacherous staircase. The kitchen was bright, but the rest of the rooms of the house were dark. There was garbage everywhere. On the coffee table in the living room was a half-completed jigsaw puzzle. It was assembled enough for me to see that it depicted a naked woman. I remember imagining the couple working on it together and that when it was completed, they’d be so aroused that they’d tear each other’s clothes off and have horrifying sex. I was too young to be imagining such things.Continue reading “ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY NINE”

ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY EIGHT

ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY SEVEN

John Luther Adams, Inuksuit. Discovered by way of Radiolab via Meet the Composer.

ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY SIX

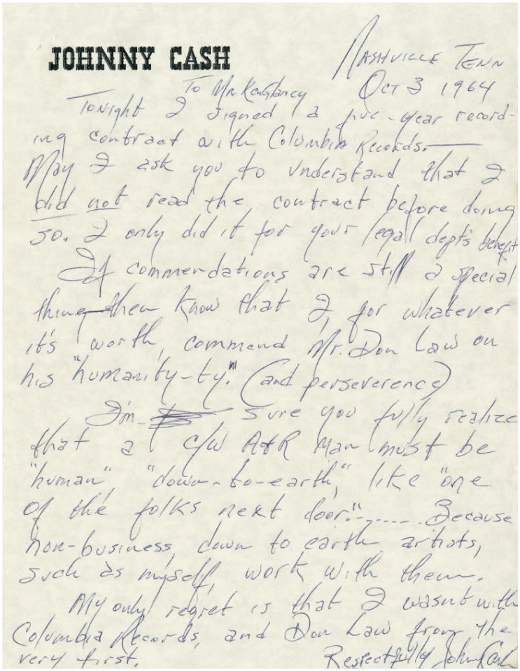

I don’t have the luxury of writing notes by hand anymore — the time it would take to digitize the volumes of notebooks I’d produce would just be overwhelming. So, I’ve switched to typing in lectures, sacrificing quality for the Command-F function.

There’s still something so beautiful about reading someone else’s handwriting though.

May I ask you to understand that I did not read the contract before doing so. I only did it for your legal dept’s benefit.

Johnny Cash, 1964, from Letters of Note.

ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY FIVE

Sesquipedalian, from Love + Radio.

ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY FOUR

From Letting Go by Atul Gawande in The New Yorker.

In 1985, the paleontologist and writer Stephen Jay Gould published an extraordinary essay entitled “The Median Isn’t the Message,” after he had been given a diagnosis, three years earlier, of abdominal mesothelioma, a rare and lethal cancer usually associated with asbestos exposure. He went to a medical library when he got the diagnosis and pulled out the latest scientific articles on the disease. “The literature couldn’t have been more brutally clear: mesothelioma is incurable, with a median survival of only eight months after discovery,” he wrote. The news was devastating. But then he began looking at the graphs of the patient-survival curves.

Gould was a naturalist, and more inclined to notice the variation around the curve’s middle point than the middle point itself. What the naturalist saw was remarkable variation. The patients were not clustered around the median survival but, instead, fanned out in both directions. Moreover, the curve was skewed to the right, with a long tail, however slender, of patients who lived many years longer than the eight-month median. This is where he found solace. He could imagine himself surviving far out in that long tail. And he did. Following surgery and experimental chemotherapy, he lived twenty more years before dying, in 2002, at the age of sixty, from a lung cancer that was unrelated to his original disease.

“It has become, in my view, a bit too trendy to regard the acceptance of death as something tantamount to intrinsic dignity,” he wrote in his 1985 essay. “Of course I agree with the preacher of Ecclesiastes that there is a time to love and a time to die—and when my skein runs out I hope to face the end calmly and in my own way. For most situations, however, I prefer the more martial view that death is the ultimate enemy—and I find nothing reproachable in those who rage mightily against the dying of the light.”

I think of Gould and his essay every time I have a patient with a terminal illness. There is almost always a long tail of possibility, however thin. What’s wrong with looking for it? Nothing, it seems to me, unless it means we have failed to prepare for the outcome that’s vastly more probable. The trouble is that we’ve built our medical system and culture around the long tail. We’ve created a multitrillion-dollar edifice for dispensing the medical equivalent of lottery tickets—and have only the rudiments of a system to prepare patients for the near-certainty that those tickets will not win. Hope is not a plan, but hope is our plan.

ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY THREE

From Gonzo:

“Whenever I think of law school, I think of those toys we had when we were kids where you use the lever to push Play-Doh through the piece that turns it into pasta or whatever other shape.”

ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY TWO

ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY ONE

Angie Wang, Soft War in Silk World.