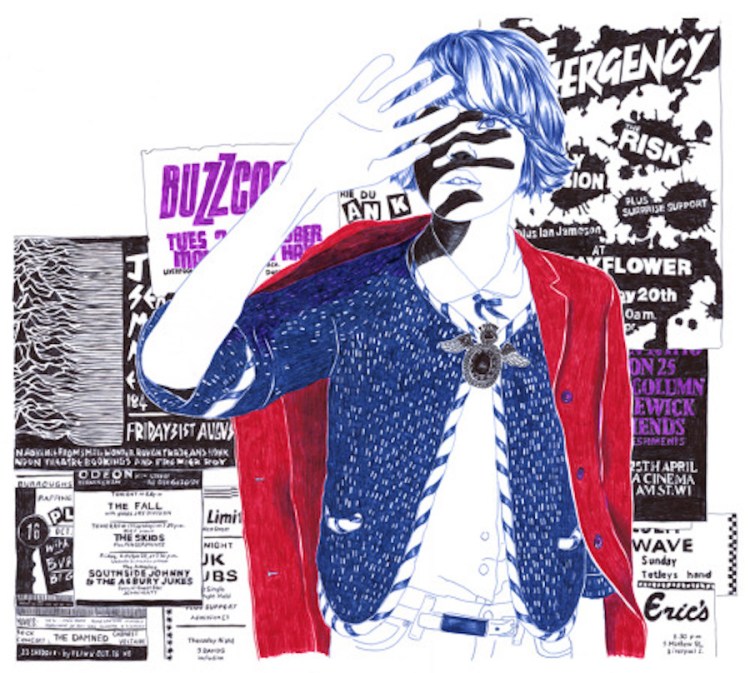

This post from Valerie Aurora, Mary Gardiner and Leigh Honeywell is so perfect. In addition to the long list of powerful and important recommendations for doing away with “rock star” culture they’ve put forward, there’s one small thing I’d like to add.

In a world run by rock stars, we need to keep an eye out for the new girl.

Given their disproportionate access to travel opportunities, financial resources and publicity, rock stars are often in the best position to spot new talent. As self-appointed spokespeople for organizations and movements, they are also often the first point of contact for people who are just starting out, or new in town.

This means that rock stars are often unofficial gatekeepers to an entire community or industry. They not only get to decide who’s “in” and who’s “out,” but have privileged access to an endless stream of new victims to choose from. Once “in,” the rock star also has special power to manipulate a newcomer’s experience, role and relationships within the community.

I have rarely seen rock stars promote the work or talent of others, but when they do, it’s often to justify bringing a new potential victim into the fold. In communities that are difficult to access or where newcomers need to be “vouched for,” a rock star’s endorsement often lets a newcomer skip to the front of the line.

Rock stars will leverage their status to take the newcomer places she wouldn’t otherwise have access: intimate meetings, secret channels, private parties.* They will introduce her to other influential, talented and interesting people in the community. Rock stars create an illusion that they alone control entry to this world, and that they are universally loved within it.

Because rock stars maintain power by managing impressions, the newcomer will rarely be left unattended, and may be kept artificially separate from potential allies. The newcomer is also often the new girl (a younger woman) brought in by a rock star (often a man who has sex with women). She may be rumoured to be, or introduced as, the rock star’s lover——creating additional layers of complexity and vulnerability. (This can also occur in different combinations of genders and sexualities, but this is the most common case.)

“Rock stars love “dating” people they have power over because it makes it easier to abuse or assault them and get away with it.” (from No More Rock Stars)

Even when there’s no illusion of a romantic relationship, that proximity can make it easy to develop a reputation as the rock star’s “new toy” or “sidekick”——words that reinforce sexist stereotypes about women as accessories, as lacking the ability to make meaningful contributions of their own. These labels may mean that newcomers are not taken seriously, or even resented by under-recognized members of a group. Most of all, it can discourage established members who might be critical of the rock star from forging a relationship with the newcomer, further contributing to their isolation.

All of these factors conspire to mean that if the newcomer is subject to manipulation, abuse or violence, there aren’t many options on the table. They may feel indebted to the rock star or incapable of speaking up. They may be convinced that the legitimacy of their membership in the group hinges on loyalty to their abuser, or that they wouldn’t belong without his approval. He may tell them outright that they have no legitimacy in the community because their access is through him. They are faced with a choice: shut up or leave. In either case, it’s an extraordinary loss.

“We have been in this position – of being powerless against rock stars… we have all mourned the spaces that we have left when they have become unliveable because of abuse.” (from No More Rock Stars)

We need to look out for newcomers, and maybe especially for the new girl. Whether through structured peer mentorship, open working groups, or prompt and meaningful integration into affinity groups, newcomers need to be able to forge relationships away from, and with others than the person who brought them in initially. We need to build organizations where volunteer intake and hiring practices are transparent, and where resources are invested to orient newcomers properly. Finally, we need to reject systems that rely on opaque processes, suspicion and star power to determine who belongs——the the kinds of systems that allow rock stars to pick and prey on new victims in the first place.

—

I’m long past being “the new girl,” but I’m young enough to remember the fear and doubt I felt at seventeen. I’m also devastated to realize that I can’t even count how many (talented, brilliant, incredible) women I’ve seen since that time in precisely the same situation: stuck somewhere between shut up and leave. I no longer want to be a bystander in that process, and can do more to make the communities that I’m part of welcoming and safe. I hope this is some small contribution to that process.

New girl, I’ve got your back.

LG

[warm thanks to both Leigh Honeywell and Valerie Aurora for their feedback and comments on this piece — Valerie in particular has expressed willingness to review other posts if you’d like to share your thoughts too]

* (or even phone calls with Julian Assange—see Phoenix’s story here)